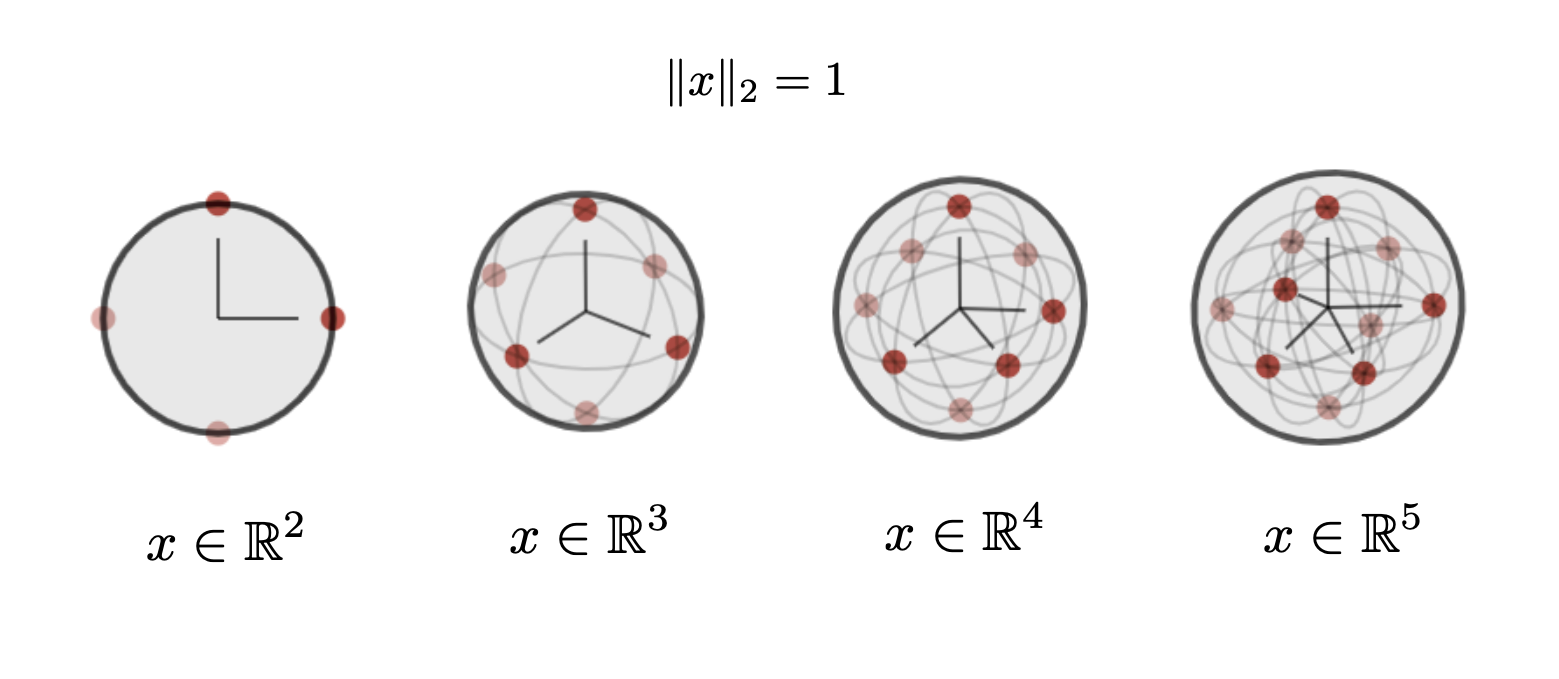

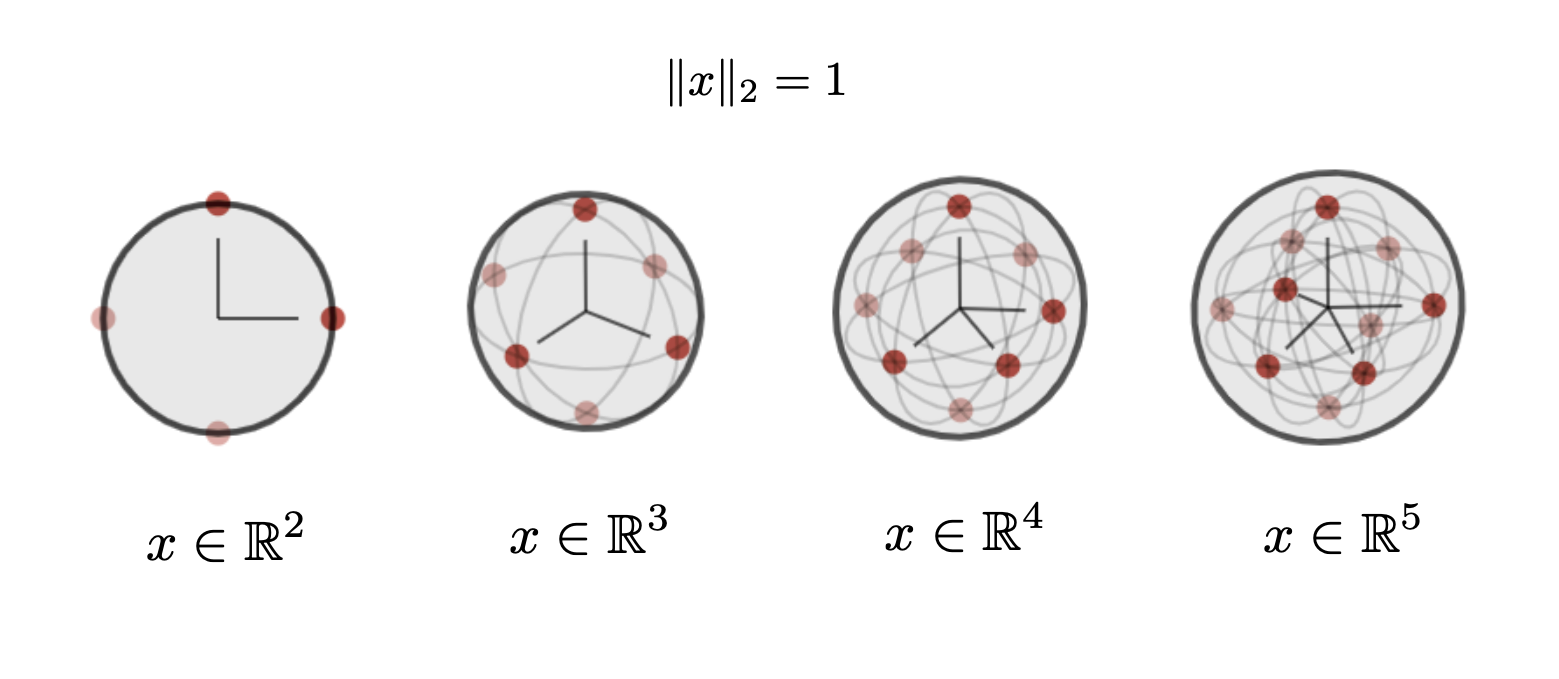

The norm of a vector is it's length. The traditional intuitive (Eucliidean) notion of length is what is called the "2-norm" given by $$ \Vert x \Vert_2 = \left(\sum_i |x_i|^2 \right)^{\tfrac{1}{2}} $$ In two dimensions, this is just the Pythagorean theorem. It can be derived for higher dimensions using iterative applications of the Pythagorean theorem. A vector with norm (length) 1 is called a unit vector. A unit vector with the same direction of any vector \(x\) can be determined by scaling \(x\) by \(\tfrac{1}{\Vert x \Vert_2}\) to get a unit vector of the form \(\tfrac{1}{\Vert x \Vert_2}x\). The set of unit vectors (for a particular norm) is called the unit ball. For a particular norm \(\Vert \cdot \Vert \), this set (in \(\mathbb{R}^n\)) is given by $$ \Ocircle_n = \Big\{ x \in \mathbb{R}^n \ \Big| \Vert x \Vert = 1 \ \Big\} $$ For the 2-norm, this is circle (or sphere) with unit radius (shown below in two, three, four, and five dimensions).

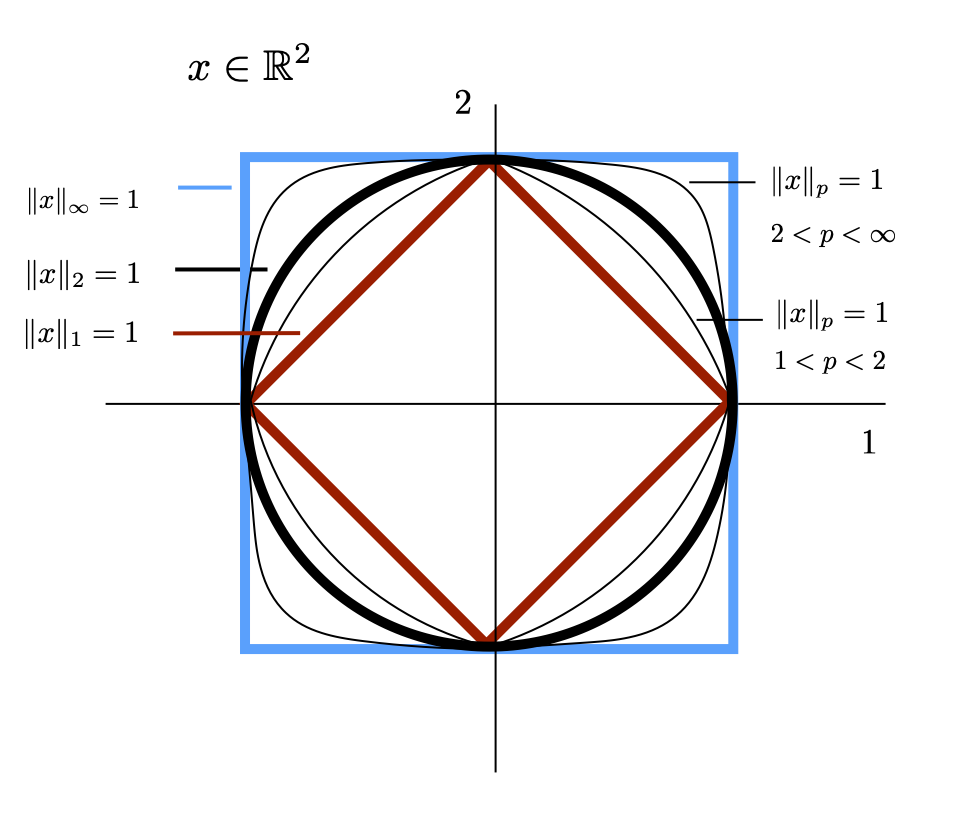

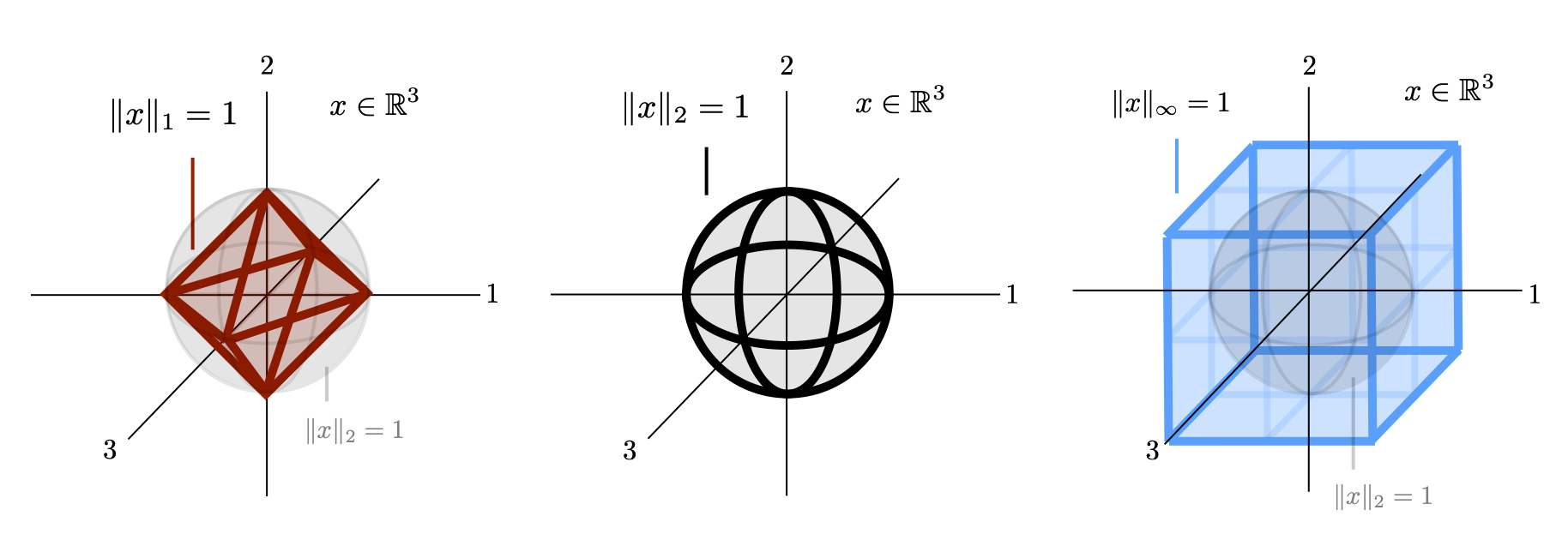

There are many other notions of length that are consistent. The idea of a "\(p\)-norm" for \( 1 \leq p \leq \infty \) is quite useful. $$ \Vert x \Vert_p = \left(\sum_i |x_i|^p\right)^{\tfrac{1}{p}}, \qquad 1 \leq p \leq \infty $$ In particular along with the "2-norm" we often use the "1-norm" and the "\(\infty\)-norm" given as $$ \Vert x \Vert_1 = \sum_i |x_i| $$ $$ \Vert x \Vert_2 = \left(\sum_i |x_i|^2\right)^{\tfrac{1}{2}} $$ $$ \Vert x \Vert_\infty = \left(\sum_i |x_i|^\infty\right)^{\tfrac{1}{\infty}} = \max_i |x_i| $$ where the \(\infty\)-norm is defined using the appropriate limit as \(p \rightarrow \infty\). The unit balls for each of these norms are shown below. The unit balls of general \(p\)-norm balls fills the space in between as shown.

The "size" of different norm balls becomes more disparate as the dimension of the space grows. For low dimensional spaces the above pictures are informative. For higher dimensional spaces, it should be noted that the unit ball of each norm agrees at the standard basis vectors \(I_i\), ie. at the axes. The uniform vector of the form \(\mathbf{1}\alpha\) shows the largest disparity between norms. To illustrate, this we can compute the 2-norm for the uniform vector in each of the other norm balls in \(\mathbb{R}^n \). For the 1-norm, the uniform vector in the unit ball is the vector \( \tfrac{1}{n}\mathbf{1} \). The 2-norm of this vector is $$ \left\Vert \tfrac{1}{n}\mathbf{1} \right\Vert|_2 = \left(\sum_i \left| \tfrac{1}{n^2}\right|\right)^{\tfrac{1}{2}} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{n}} $$ which approaches 0 (sublinearly) as \(n \rightarrow \infty\). Similarly, for the \(\infty\)-norm, the uniform vector in the unit ball is simply \(\mathbf{1} \) The 2-norm of this vector is $$ \left\Vert \mathbf{1} \right\Vert|_2 = \left(\sum_i \left| 1^2\right|\right)^{\tfrac{1}{2}} = \sqrt{n} $$ which approaches \(\infty\) (again, sublinearly) as \(n \rightarrow \infty\).

Similarly, the volume and surface area of unit balls in higher dimension exhibit somewhat counter intuitive behavior. The formulas for these are significantly more complicated.

Note: this section is better understood with background in positive definite matrices.

Another class of norms (that expands the 2-norm) is defined by positive definite matrices. For a positive definite symmetric matrix \(P \succ 0\), \(P=P^T \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}\), we can define a norm via the quadratic form with \(P\) given by $$ \Vert x \Vert_P = \big(x^TPx\big)^{\tfrac{1}{2}} $$ Level sets of this norm are ellipsoidal as shown below. (For more details, see the section on quadratic forms and positive semidefinite matrices.) One can think of a \(P\)-norm as simply the 2-norm after the vector space has been stretched by a particular (positive definite) coordinate system. Explicitly, if we define \(x = P^{-\tfrac{1}{2}}x'\) then the \(P\)-norm is just the 2-norm in the \(x'\) coordinates since $$ x^TPx = x'^TP^{-\tfrac{T}{2}}PP^{-\tfrac{1}{2}}x' = x'^Tx' $$ Intuitively since we can write the above coordinate transformation as \(x' = P^{\tfrac{1}{2}} x\), we can think of the matrix \(P\) (or really \(P^{\tfrac{1}{2}}\)) as transforming the space before the 2-norm is applied.

A definition of an inner product defines a norm that is said to be "induced" by the inner product. For inner product \(\langle \cdot, \cdot \rangle \), the induced norm is given by $$ \Vert x \Vert| = \big(\langle x, x \rangle \big)^{\tfrac{1}{2}} $$ For the standard Euclidean inner product, this is simply the 2-norm. For the \(P\)-inner product, \( \langle \cdot, \cdot \rangle_P \), this gives the \(P\)-norm, \(\Vert \cdot \Vert|_P\).