Note: this section is better understood with a clear understanding of matrices.

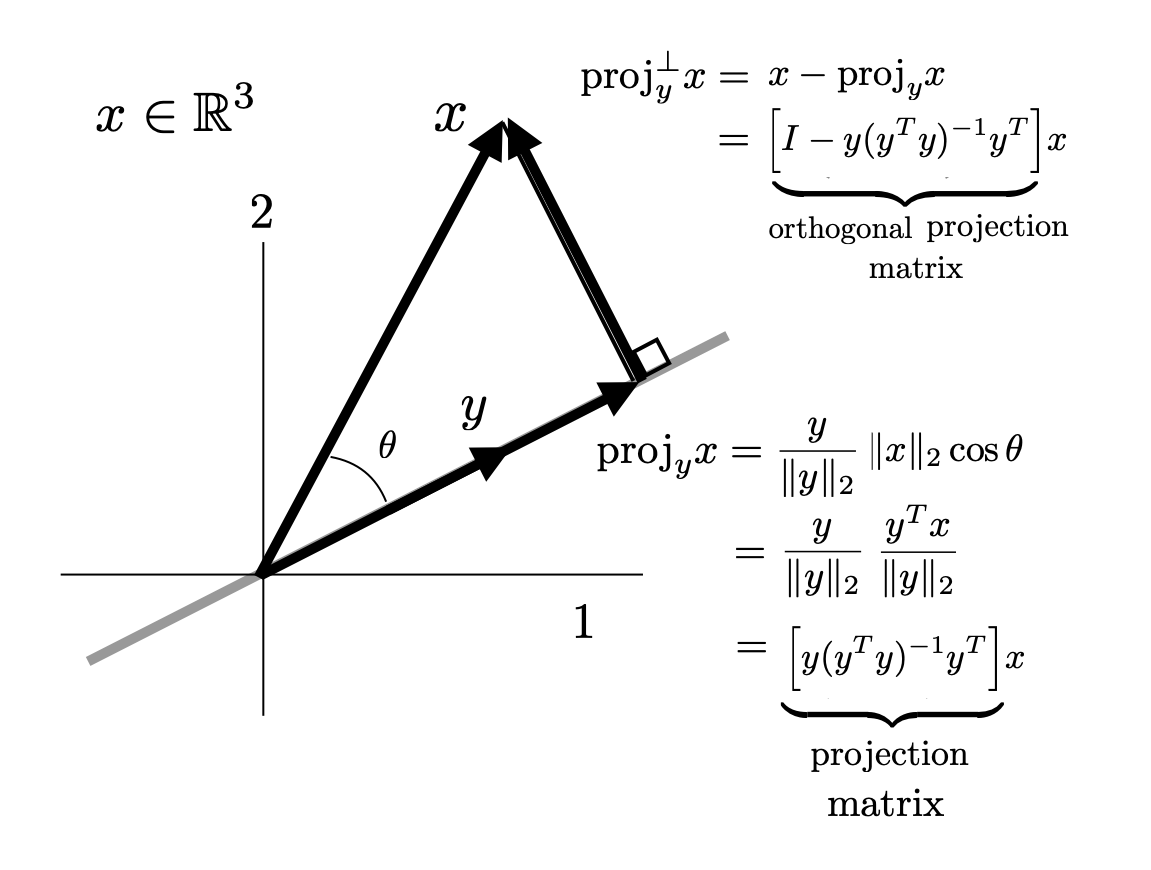

Projection onto a VectorOne of the fundamental uses of inner products is to compute projections. A projection of a vector \(x\) onto \(y\), which we can denote \({proj}_{y}x\), is the closest vector to \(x\) that points precisely in the \(y\) direction. We illustrate this in the figure below.

Intuitively one can see that the difference between \(x\) and \({proj}_y x\) must be orthogonal to \(y\). (Mathematically, this comes from the Pythagorean theorem applied to \(x-{proj}_y x\)). We can also see intuitively that the length of the projection is \(\vert|x\vert|_2 \cos \theta\) where \(\theta\) is the angle between \(x\) and \(y\) and can thus be related to the inner product using the geometric definition \(y^Tx = \vert|x\vert|_2\vert|y\vert|_2 \cos \theta\) If a vector \(y\) is a unit vector, than the geometric definition of an inner product gives that the length of the projection is simply \(y^Tx\). Algebraically, then, the process of computing a projection is can be done by converting \(y\) to a unit vector (ie. \(\tfrac{y}{\vert|y\vert|_2} \)) taking the inner product with \(x\) to get the length of the projection and then multiplying that length by the unit vector again in the \(y\) direction. Formulaically, we have that $$ {proj}_y x = \left(\frac{1}{\vert|y\vert|_2}y\right)\left(\frac{1}{\vert|y\vert|_2}y^Tx\right) = y(y^Ty)^{-1}y^T x $$ The second version in the equation above is elegant in that it explicitly writes the projection operator as a matrix that we can then use to project any vector \(x\) onto \(y\). We can denote this matrix \({proj}_y = y(y^Ty)^{-1}y^T \). We will also see that this form is directly extendable to projecting onto a subspace of dimension greater than one.

If we want to get the component of \(x\) orthogonal to \(y\) we can simply subtract the projection from \(x\). This can be called the projection orthogonal to \(y\). $$ {proj}_y^\perp x = x- y(y^Ty)^{-1}y^T x = \Big[ I-y(y^Ty)^{-1}y^T \Big]x $$ Note that again we have managed to write the projection operation as a matrix which we can denote \( {proj}_y^\perp = I-y(y^Ty)^{-1}y^T \).

It is instructive to check that for any \(x\), \({proj}_y x\) and \({proj}_y^\perp x\) are orthogonal to each other. We can check this actually independent of \(x\) as follows $$ \big({proj}_y x \big)^T {proj}_y^\perp x = x^Ty(y^Ty)^{-1}y^T\big( I-y(y^Ty)^{-1}y^T \big)x $$ $$ = x^T\Big(y(y^Ty)^{-1}y^T- y(y^Ty)^{-1}y^Ty(y^Ty)^{-1}y^T \Big)x $$ $$ = x^T\Big(y(y^Ty)^{-1}y^T- y(y^Ty)^{-1}y^T \Big)x = x^T(0)x = 0 $$ Note the fact that \({proj}_y({proj}_y) = {proj}_y\).

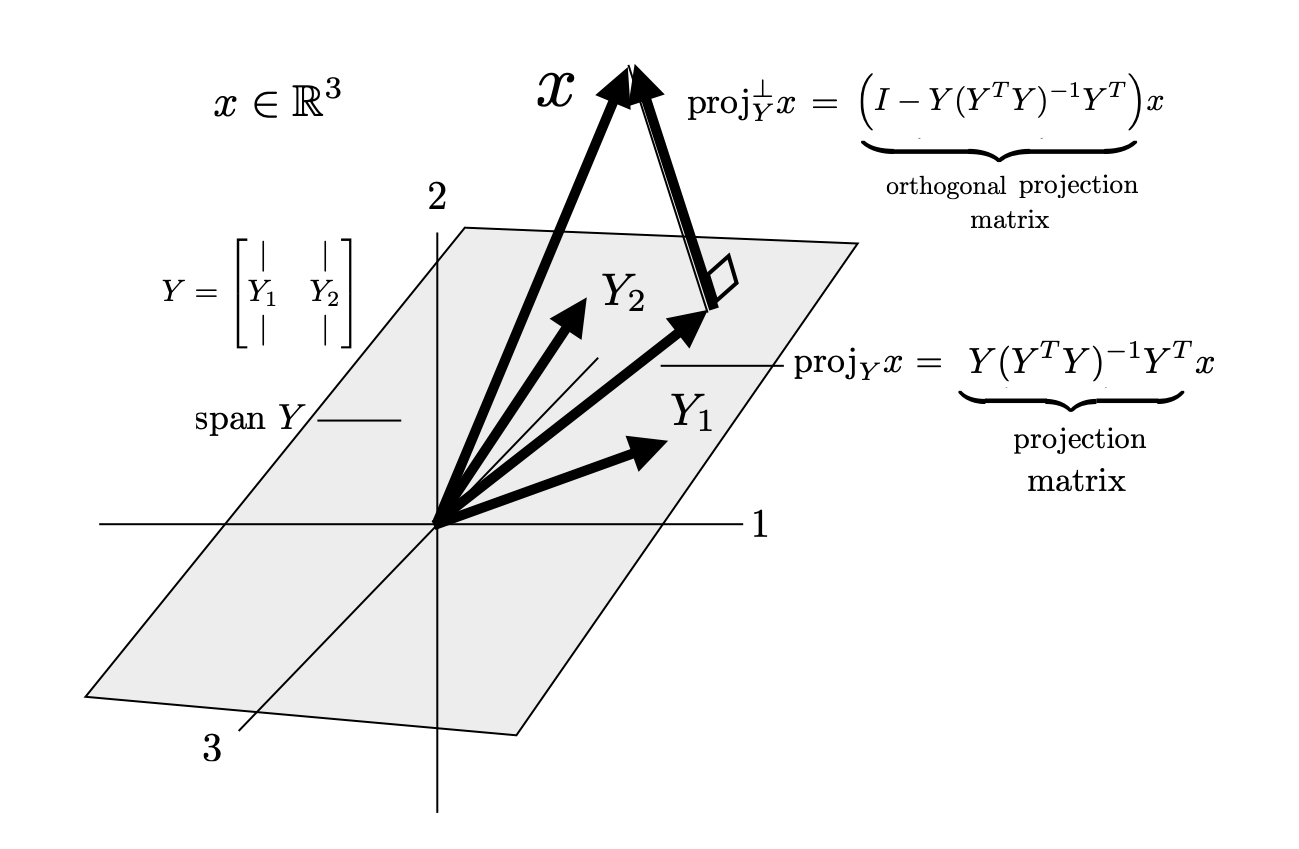

A similar formulation works if we would like to project \(x\) onto a a subspace spanned by multiple vectors given by the columns of a matrix \(Y \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n} \) $$ Y = \begin{bmatrix} | & & | \\ Y_1 & \cdots & Y_n \\ | & & | \end{bmatrix} $$ We will assume for this discussion the columns of \(Y\) are linearly independent and we will denote this as \({proj}_Y x\).

As in the one dimensional case above, we proceed by converting columns of \(Y\) into unit vectors, but for multi-dimensional subspaces there is another subtlety; we must make the columns of \(Y\) orthogonal to each other as well. To see this consider a counter-example for two vectors \(Y_1\) and \(Y_2\). A naive approach would be to normalize each vector \(Y_i\), project \(x\) onto each and add up the projections according to the formula $$ {proj}_Y x = {proj}_{Y_1}x + {proj}_{Y_2}x $$ This is, in general, an incorrect approach as illustrated in the left figure below Unless, \(Y_1\) and \(Y_2\) are orthogonal to each other the result will not give the desired projection. If, however, the columns of \(Y\) are orthonormal as illustrated in the right figure.

The process of orthonormalizing the columns of \(Y\) is more complicated than normalizing a single vector. We will discuss this in much more detail in the section on orthonormalization and in the section on shape matrices and polar decomposition. For now we will simply give the following formula. If we take $$ U = Y(Y^TY)^{-\tfrac{1}{2}} $$ the columns of \(U\) are orthonormal to each other and span the same space as \(Y\). Critically, we can check that the columns of \(U\) are orthonormal by taking all the pairwise inner products of each column. $$ U^TU = (Y^TY)^{-\tfrac{1}{2}}Y^TY(Y^TY)^{-\tfrac{1}{2}} = I $$ Here we note that the matrix \((Y^TY)^{\tfrac{1}{2}}\) is invertible if and only if the columns of \(Y\) are linearly independent. We note also that there is a specific relationship between the columns of \(U\) and \(Y\) that we will discuss more in later sections. We then can compute the projection of \(x\) onto the span of \(Y\) by projecting \(x\) onto each column of \(U\) and summing up. $$ {proj}_y x = U_1U_1^Tx + \cdots U_nU_n^Tx = UU^Tx $$ Note that the second equality is based on the outer product formulation of matrix multiplication. Expanding this out in terms of the original matrix \(Y\) now gives $$ {proj}_y x = Y(Y^TY)^{-\tfrac{1}{2}}(Y^TY)^{-\tfrac{1}{2}}Y^Tx =Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^Tx $$ Here we can denote the projection matrix as \({proj}_Y = Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T\). Note the similarities to the one-dimesional form and specifically the similar role of \((y^Ty)^{-1}\) and \((Y^TY)^{-1}\) in the two formulas.

Similarly, we can compute a projection orthogonal to the span of \(Y\) as $$ {proj}_Y^\perp x = x - Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^Tx = \big(I - Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T\big)x $$ with projection matrix \({proj}_Y^\perp = \big(I - Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T\big)\). Finally, we can check again algebraically that for any \(x\), \({proj}_Y x\) and \({proj}_Y^\perp x\) are orthogonal (as desired) regardless of what \(x\) is. $$ \big({proj}_Yx\big)^T{proj}_Y^\perp x = x^T Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T\big(I - Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T\big)x $$ $$ = x\big(Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T- Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^TY(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T\big)x $$ $$ = x\big(Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T- Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T\big)x = x^T(0)x = 0 $$ We now give a detailed visualization of the process discussed above.

Generally in math, a projection operator is an operator such that applying the operator twice yields the same result as applying it once, ie. $$ ({proj}_Y)({proj}_Y) = {proj}_Y $$ This is enough to imply the orthogonality conditions we expect above since it implies that $$ \big({proj}_Yx\big)^T \big(I-{proj}_Y\big)x = x^T\big({proj}_Y-({proj}_Y){proj}_Y\big)x = x^T\big({proj}_Y-{proj}_Y\big)x = x^T(0)x = 0 $$ We also can check that this true for for the matrix operators above $$ {proj}_Y({proj}_Y) = Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^TY(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T = Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T= {proj}_Y $$ and $$ {proj}_Y^\perp({proj}_Y^\perp) = \big(I- Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T\big) \big(I- Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T\big) $$ $$ = I- 2Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T + Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^TY(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T $$ $$ = I- 2Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T + Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T = I- Y(Y^TY)^{-1}Y^T = {proj}_Y^\perp $$